Carmel Cacopardo, ADPD-The Green Party Deputy Chairperson submitted the party’s proposals for the Malta Transport Master Plan 2030. The public consultation closed on the 9 of December.

***

ADPD-The Green Party

The National Transport Master Plan 2030 Public Consultation

Introduction

This submission consolidates ADPD-The Green Party’s policy on mobility and transport. It focuses on reclaiming the streets, reassigning road space and better people-centric communities. It focuses on community rather than egoistic individualism which promotes the status quo and blames everything on ‘others’. This document will focus mostly on land-based mobility within the country.

It must be pointed out however that if the Transport Master Plan is really directed towards “embedding climate adaptation, renewable energy, and low emission transport into infrastructure planning while ensuring efficiency of the transport system”, expanding airport capacity, and so increasing incoming tourists, and the continued focus on parking and wider roads contradicts this aim.

The consultation document makes some good observations, but then contradicts itself when it continues to promote spending on more space for cars. It is all well and good to state that micromobility and public transport are space efficient, cleaner and to be encouraged, but then the consultation document pushes these modes of transport off the roads to make more and more space for cars.

The Transport Malta document acknowledges that the government’s focus is on increasing motor vehicle capacity by widening roads, but at the same time the failure of this strategy is clear: “it is sometimes difficult to increase motor vehicle capacity by road widening or new road building here, so the general approach, in this case, is to increase road capacities through measures to enhance the number of travellers passing through the link rather than the number of vehicles”. The shift in focus, and so in investment, towards public transport and active mobility and away from road widening for more cars should be spelt out clearly without any ifs or buts.

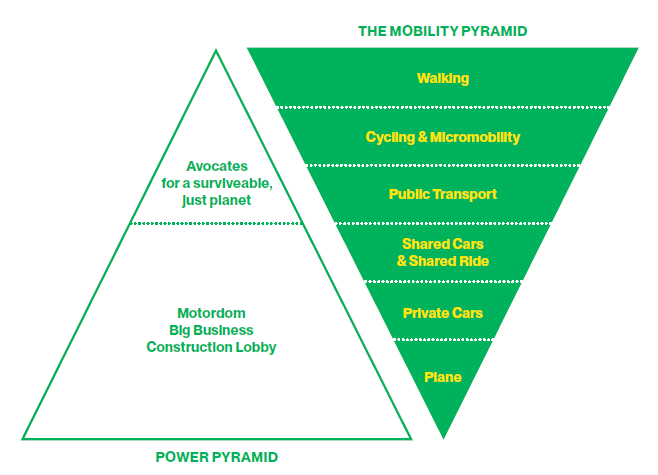

The Mobility Pyramid

The key to an effective National Transport Policy 2030 is the embracing of the now well known and well researched Mobility Pyramid. A study led by EIT Urban Mobility (Costs and benefits of the urban mobility transition – 2nd edition, October 2024) shows that active mobility, that is walking and cycling in urban areas, provides major health and economic gains. It shows that active travel could deliver between €850 and €1,170 in health benefits per person, with even small increases in physical activity producing significant long-term public health savings. The study identifies public transport as the backbone of a sustainable mobility system. Investment in efficient and reliable transit could reduce car use, and improve road safety. Shared mobility options like bike-sharing and car-sharing help connect users to transit. Active mobility, including personal bicycles, pedelecs and scooters, together with proper infrastructure and strictly enforced speed limits on residential roads is also key to a successful shift in a mindset which prioritizes cars, pollution and the occupation of public space by cars, over healthy, welcoming and beautiful towns and cities. This means PRIORITISING and REASSIGNING space in urban areas and our roads to these forms of mobility. The Mobility Pyramid must be translated in practice. This task may not be easy, there will be resistance by vested interests, by those who are used to their politicians bending over backwards to satisfy their self-centred egoistic interests, and by commercial lobbies.

Embracing the mobility pyramid, prioritising active travel, public transport, and shared mobility over private cars, offers substantial economic, environmental and health benefits, including over 90% greenhouse-gas reductions by 2050. This means pairing infrastructure upgrades with strong regulatory measures. The Transport Malta consultation document makes good observations about the situation on our roads and acknowledges that “some drivers in Malta exhibit aggressive driving behaviour with little regard for cyclists and pedestrians. The lack of awareness about sharing the road with non-motorised traffic poses a serious safety risk”, for example. Hence the need for effective enforcement, and investment to make urban roads safer, while providing good infrastructure to encourage micromobility, especially since according to the consultation document itself travel distances average a meagre 6.1km.

Public Transport and integration with other forms of mobility

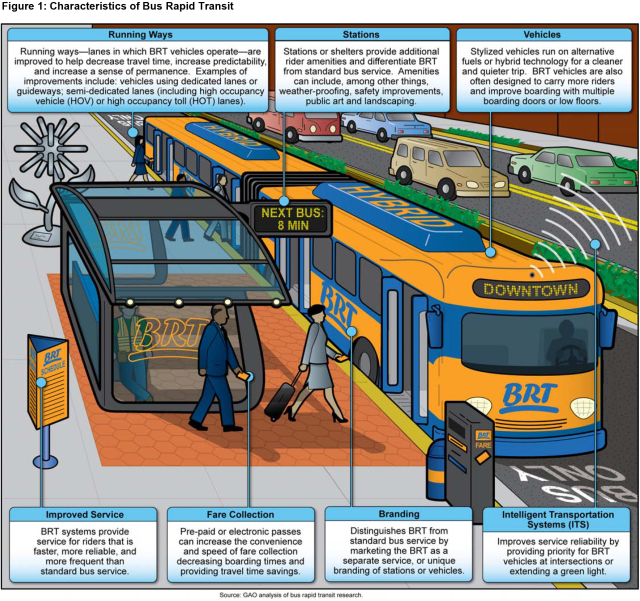

Governments have ignored reports they themselves commissioned. One such report is the Halcrow Report which, back in 2007, recommended a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system for high demand ‘transport corridors’. The mentality of preserving the status quo, and so the refusal to reassign road space from private cars to the exclusive use of public transport is probably the main reason for politicians ignoring this report. Instead they come up with ideas which reveal a certain lack of understanding of basic urban and transport development and policy. One such a vacuous idea is the metro, sometimes even with the even crazier undersea tunnel to Gozo latched onto it. The underlying reasoning is crystal clear here: ‘we will not change anything on the surface, you will be able to continue as is’. That would be a total failure, billions upon billions of Euro spent with no results. There are other issues with metros, including the very short distances in such a small country, the massive amount of energy needed for ventilation, issues with flooding and extreme heat, not to mention huge maintenance costs and maintenance depots needed. No system is a panacea however, various recent studies including Malta-centred studies show that BRT offers the best solution for Malta (Attard, M., 2023. Planning for Bus Rapid Transit in an island context. The challenges of implementing BRT in Malta, Research in Transportation Economics). Behavioural change is necessary and investment in incentives and disincentives should reflect this.

Advantages include significantly lower capital costs, faster implementation, greater flexibility, and strong social, environmental and economic paybacks. The astronomical fixed costs of the metro are a major issue. It imposes heavy fiscal and social burdens on the country, and may become a convenient excuse to retain the status quo on our streets and urban areas. A strategy combining BRT with feeder bus services, including park-and-ride and active mobility connections and services offers optimal overall transit investment.

The integration of BRT with other car-free modes of mobility is essential (Moinse, D.,2024. A Systematic Literature Review on Station Area Integrating Micromobility in Europe: A Twenty-First Century Transit-Oriented Development. In: Belaïd, F., Arora, A. (eds) Smart Cities. Studies in Energy, Resource and Environmental Economics). Research consistently shows that improving bicycle parking is one of the most effective measures for encouraging bicycle use, especially as part of multimodal trips. Adequate, secure, and conveniently located parking facilities increase the likelihood that cyclists will access public transport by bike. Studies in the Netherlands demonstrate that the availability of bicycle stands influences the choice of departure stations, while insufficient or unsafe parking is a major barrier. Providing secure options such as lockers and cameras can significantly boost bike-and-ride uptake, and high-quality bus systems, such as BRT systems also benefit from enhanced bicycle parking.

For Malta, BRT offers an attractive solution because of:

• Much lower capital cost and faster delivery. Well-designed BRT can deliver metro-like benefits (speed, reliability) at a fraction of the cost and within a shorter time window. Transport Malta’s own strategic study identified BRT as having “great scope” for the island’s main corridors (https://www.transport.gov.mt/Malta-Bus-Rapid-Transit-Feasability-Report-by-Halcrow-Group-Limited-2007.pdf-f1694).

• Operational flexibility. BRT permits branching, feeder integration and incremental capacity increases (more/longer buses) without the fixed route permanence and high sunk costs of rail-based transport.

• Street-level integration and equity. Properly designed BRT with dedicated lanes, off-board fares and level boarding can speed journeys and benefit intermediate destinations directly, improving access for outlying neighbourhoods and Gozo-Malta connections (via feeder services) without large capital outlays. The ability to run electric or hybrid buses also reduces local emissions quickly.

Conclusion

The National Transport Master Plan consultation document, while making some good observations about the state of mobility in Malta, still seems to shy away from committing to the necessary action needed. While acknowledging the difficulties and resistance to change, it seems to rely on ‘raising awareness’ about problematic issues rather than proposing different scenarios with different policy actions and their results.

The consultation document concludes: “The path to 2030 is not without obstacles, but with collective effort and unwavering commitment, Malta can achieve its transport objectives and set a benchmark for sustainable development in the region. This Plan represents a shared vision—a call to action for government, industry, and society to work together to create a transport system that enhances the quality of life for all Maltese citizens while safeguarding the natural heritage for future generations.”

We share this vision. However we want to see a clear commitment to actually work towards this vision. The Minister for Transport constantly contradicts and undermines the vision professed by Transport Malta.

Our proposals are aimed to achieve a sustainable, people-first mobility through targeted and focused actions. Time is up.

Summary – A Sustainable, People-First Mobility Policy for Malta

Vision

A transport system that reduces dependence on private cars, prioritises people over vehicles, and delivers efficient, safe, and inclusive mobility across Malta and Gozo. The Mobility Pyramid guides mobility policy decisions.

Strategic Objectives

- Achieve a national modal shift — prioritise public transport, walking, cycling and shared modes.

- Enhance public transport performance — reliability, speed, and frequency through BRT on high volume routes.

- Design people-friendly streets and 15-minute neighbourhoods.

- Promote environmental sustainability and climate alignment through reduced car use.

Key Policy Actions

- Develop Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors and dedicate road space to public transport.

- Build a safe, connected cycle-lane network including “bicycle superhighways” connecting heavily frequented destinations.

- Implement congestion pricing in dense areas; reinvest revenue into sustainable mobility.

- Pedestrianise central squares and urban cores.

- Roll out national EV charging infrastructure, prioritising public accessibility.

- Enforce safe speed limits and universal design for vulnerable users.

Implementation Approach

- Use participatory planning with local councils and civil society.

- Allocate budgets based on modal shift targets.

- Link land-use planning with transport objectives (15-minute city principles).

- Monitor progress through annual sustainable mobility indicators.

Benefits

- Reduced congestion and air pollution.

- Improved public health and safety.

- Stronger community life and local economies.

- Contribution to Malta’s climate and sustainability goals.